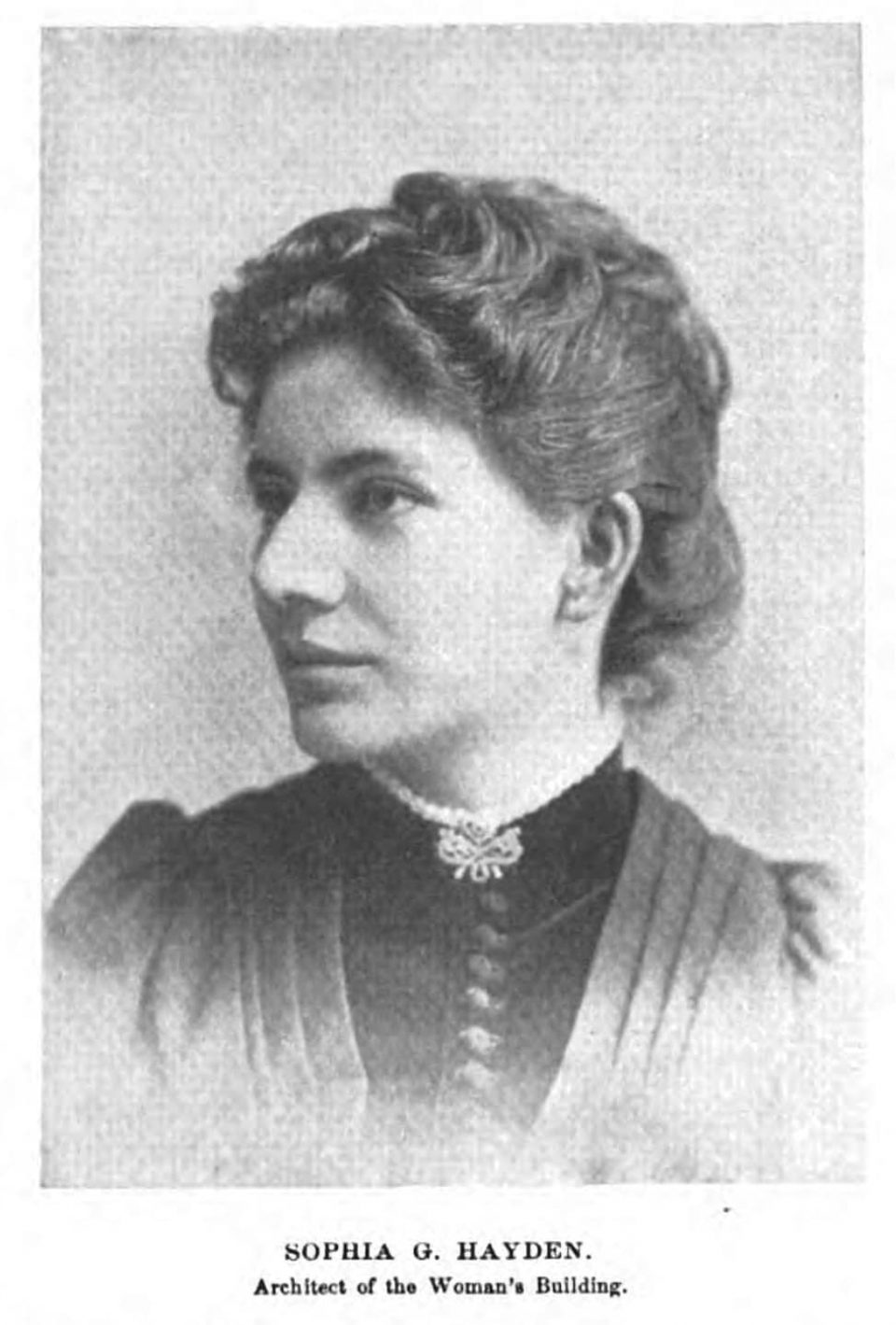

Thoughout her architectural career, which lasted only a few years and resulted in only one realized building, Sophia Hayden Bennett (1868–1953) played an important role in the profession at the moment when women were beginning to practice in the United States.11The major sources of information on the life and career of Sophia Hayden Bennett include Madeleine B. Stern, We the Women (New York: Shulte Publishing Co., 1963); Susanna Torre, ed., Women in American Architecture (New York: Whitney Library of Design, 1977); “Sophia Gregoria Hayden” in Sarah Allaback, The First American Women Architects (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2008); Charlene G. Garfinkle, Women at Work: The Design and Decoration of the Woman’s Building at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara, 1996); Judith Paine, “Sophia Hayden and the Woman’s Building,” Helicon Nine 1, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 1979): 28–37; Jeanne Madeline Weimann, “A Temple to Women’s Genius: The Woman’s Building of 1893,” Chicago History VI, no. 1 (Spring 1977): 23–33; and Virginia Grant Darney, Women and World’s Fairs: American International Expositions, 1876–1904 (Ph.D. dissertation, Emory University, 1982). Genealogical information can be found at http://onerhodeislandfamily.com/2011/10/09/remembering-sophia-hayden-bennett-part-1/ (accessed December 14, 2014). As the first woman to receive a degree in architecture from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and as the architect of the Woman’s Building at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, Hayden drew attention to the small group of female architects pursuing academic training—and to the circumstances they would confront upon entering the profession.

Sophia Hayden Bennett

Birthplace

Santiago, Chile

Education

- Hillside School

- West Roxbury High School

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology, B.Arch., 1886–90

Major Projects

- “Museum of Fine Arts,” 1890, Thesis Project, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Woman’s Building of the World’s Colombian Exposition, Chicago, 1891–93

- Memorial Building, Chicago, 1894 (unbuilt)

Awards and Honors

- Artist’s Medal, Board of the World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893

- Gold Medal, Board of Lady Managers, World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893

Location of Architect’s Archive of physical images, plans, drawings

- MIT Museum

- Chicago Historical Society

Further Information

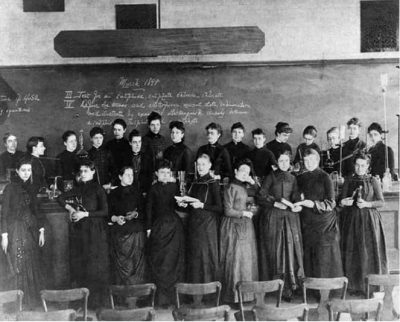

An 1888 photograph showing the twenty-four female students of MIT (and Ellen Swallow Richards, an early graduate of the institute and then its first female instructor). Sophia Hayden is at the far left of the front row, holding a T-Square as a symbol of her field of study. MIT Museum

Early Life and Education

Sophia Gregoria Hayden was born in Santiago, Chile, on October 17, 1868, to a Peruvian mother (Elezena Fernandez Hayden) and a father (George Henry Hayden) from the northeastern United States. She spent her early childhood in Chile, and was sent to Boston to live with her paternal grandparents and to attend school. Educated first at the Hillside School and then at West Roxbury High School, Hayden enrolled at MIT in 1886, the first woman admitted to the bachelor’s degree program in architecture and one of only a small cohort of women enrolled at the Institute. A photograph from 1888 shows MIT’s twenty-four female students, each holding an instrument representative of her field.

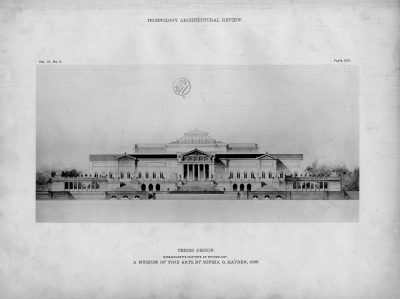

Sophia Hayden, elevation, Museum of Fine Arts, MIT thesis, 1890. Technology Architectural Review, 3, no. 5, 1890. Rotch Library, MIT

The program of study in architecture at MIT was broad. Its orientation toward professional education emphasized both practical knowledge and the academic methods of design established by the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. As the core of their training, students were taught the history of the classical orders and their application in design. Although drawing classes took up much of the curriculum (with specific studies of perspective, shadows and shading, and watercolor), students also took courses on building construction, business relations, constructive design, and contracts.22See Massachusetts Institute of Technology Annual Catalogue 1896-1897. Hayden mastered each of these subjects as she proceeded through the four years of the program, which culminated in a thesis in her final year.

For her thesis, Hayden presented a design for a Museum of Fine Arts, a civic program typical of MIT’s academic pedagogy.

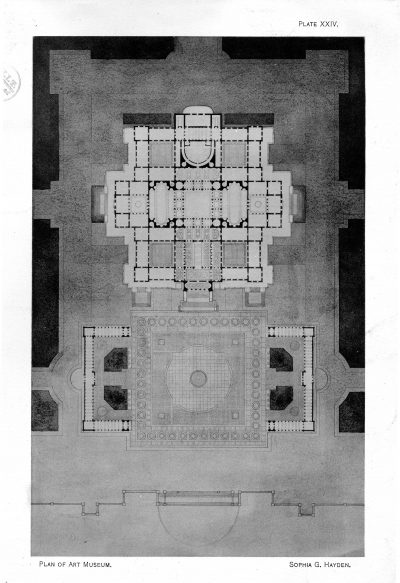

Sophia Hayden, plan, Museum of Fine Arts, MIT thesis, 1890. Technology Architectural Review, 3, no. 5, 1890. Rotch Library, MIT

Sophia Hayden, elevation drawing (This drawing is cataloged as part of Hayden’s thesis, but does not correspond to the design presented in the other drawings). MIT Museum

Drawing upon the precedents of the Italian Renaissance, but with a scale and organization reflecting a concern for procession and the distribution of diverse programmatic elements, the project reveals Hayden’s command of the design skills emphasized in her training. Her plan features a large forecourt framed by colonnades and set before a relatively sober façade. Ornamentation is gathered around the portico at the center of the façade, where a grand stair leads toward the middle of the biaxial symmetrical plan. The building’s rooms and minor courts are placed around this core. The duplication of square geometry in the forecourt and building is amplified by the further articulation of orthogonal rooms and voids according to the careful concern for proportion that Hayden’s training had instilled. The design attends to practical matters as well: Hayden’s description includes information about the accommodation of service requirements in the basement and an explanation of the building’s heating and ventilation systems.

The drawings demonstrated Hayden’s skill and aptitude.33The project was selected to appear in the Technology Architectural Review. See Technology Architectural Review 3 (1890). The details delineated in the precisely inked lines and the evocative effects of the watercolor washes were intended to convey a sensibility of design, while the disposition of volumes and the explanation of technical details also demonstrated practical knowledge. Hayden graduated with honors in 1890, the first woman to receive a bachelor’s degree in architecture from MIT.44The architect Lois Lilley Howe also completed her course of studies at MIT in 1890, but Howe was enrolled in the Institute’s two-year partial course in architecture.

Career

Following her graduation from MIT, Hayden began teaching mechanical drafting at the Eliot School, a grammar school in Boston that emphasized vocational education. It is not clear what professional openings may have been available to her, but a few months later she encountered the notice that would lead to her first architectural commission.

On February 2, 1891, the Construction Department of the World’s Columbian Exposition announced a competition for the design of the Woman’s Building, one of the exhibition halls to be constructed for the 1893 international exposition in Chicago. The competition advertisement specified that only designs submitted by women would be eligible, and that each entrant must have formal training in architecture. The author of the winning entry would be appointed as the architect of the Woman’s Building, and would receive an honorarium of $1,000 for executing its working drawings.

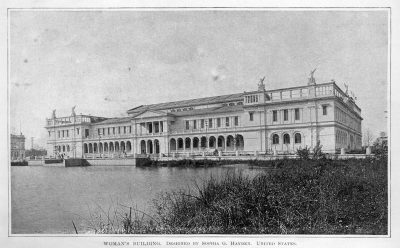

Sophia Hayden, Woman’s Building, World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. Photograph by William Henry Jackson, 1894. Ball State University Archives and Special Collections, Documents and Drawing Archive.

The terms of the competition reflected contemporary debates about women in the professions. During the last decades of the nineteenth century, a number of activist organizations had focused attention on women’s changing roles. Suffrage movements, labor groups, settlement societies, and other organizations created terms of debate that carried into the planning of the Columbian Exposition, bringing particular attention to the participation of women in professional work. Although they did not share a uniform agenda, these organizations successfully pressed for the creation of a Board of Lady Managers, headed by Bertha Honoré Palmer, to oversee the participation of women in the fair’s organization. The Board, in turn, was able to impose the requirement that the Woman’s Building be designed by a female architect. However, neither this decision nor the terms of the competition were received with unanimous approval. Some managers felt that the opportunity to hire an eminent male architect had been unnecessarily forfeited, while others believed that female architects had been slighted. Louise Bethune, the most prominent and experienced of contemporary female practitioners, refused to enter the competition because the thousand-dollar honorarium was vastly less than the commission being offered to male architects for other buildings at the fair.

Sophia Hayden did choose to submit a design, along with twelve other entrants—all under the age of twenty-five. A jury including members of the Board of Lady Managers and Daniel Burnham, the Chief of Construction for the fair, judged Hayden’s design the winner. The building she proposed closely followed the requirements specified in the competition advertisement and the indications of an accompanying sketch provided by the Board of Lady Managers. Rectangular in plan, two stories in height, the design suggested the same language of Italian Renaissance classicism that Hayden had employed in her MIT thesis, but here with less severity and adapted for construction in wood and staff rather than stone. Symmetrical wings flanked a central portico, with interior rooms surrounding a central hall.

As the author of the winning design, Hayden was awarded the commission and invited to travel to Chicago to undertake the working drawings, as specified by the competition, under the auspices of the Exposition’s Bureau of Construction. Once in Chicago, she was quickly introduced to the many contingencies of architectural practice, exacerbated by the rapid schedule of the fairgrounds’ construction. Hayden had first to deal with changes requested by the Board of Lady Managers, some based on perceived shortcomings in the proposed design and some prompted by changes to the program and contents of the Woman’s Building. Most drastically, an additional third story was required, forcing extensive alteration to the overall design. Ornamental details would be provided by a group of female artists chosen separately by the Lady Managers, and thus Hayden was not responsible for those aspects of the building. Still, she had to contend with a vast scope of work to complete the eighty-thousand-square-foot building on a constrained schedule.55For a detailed account of the artists responsible for the ornamental elements of the Woman’s Building, see Garfinkle, “Women at Work.” The Woman’s Building was one of the first fair buildings to enter into construction, during the summer of 1891, and the fact that it was finished and ready for the opening of the Exposition and within budget suggests that Hayden had mastered the managerial aspects of the profession as well as the artistic ones.

Sophia Hayden, Woman’s Building of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893

Critical reception of the Woman’s Building varied, with some reviews deeming it a mediocre design, others praising it as a notable accomplishment, and many offering a specifically gendered attribution to its architecture. For example, Henry van Brunt, an architect and critic, wrote that the building was “rather lyric than epic in character, and it takes its proper place on the Exposition grounds with a certain modest grace of manner not inappropriate to its uses and to its authorship.”66See “Architecture at the World’s Columbia Exposition” (Part IV), The Century Magazine 44, no. 5 (September 1982): 731. Its sponsors were unequivocal, regarding the design as a crucial contribution to the success of the overall program of events and exhibits organized by the Board of Lady Managers. Burnham agreed with the judgment that the Woman’s Building was one of the exemplary works of architecture at the fair, and awarded Hayden an Artist’s Medal to accompany the Gold Medal she had received from the Board of Lady Managers.

Hayden must have received public praise, too, when she attended the building’s formal dedication in October 1892. But shortly thereafter, published reports described her as suffering from exhaustion, or even a nervous breakdown, caused by the difficulties of the preceding two years’ work. While for some observers this confirmed the inadvisability of women entering into the architectural profession, Hayden’s accomplishment had nevertheless brought new attention to their efforts and capacities.

This first commission was also Hayden’s last realized building. Although she was asked to design a Memorial Building that would remain on the fair site as a permanent exhibition, and may have prepared initial plans, she did not complete any other architectural works. She returned to New England, and following marriage to portrait painter and interior designer William Blackstone Bennett, settled in Winthrop, Massachusetts. A wedding announcement stated that “both are highly esteemed and respected . . . versatile as well as talented.”77Boston Daily Advertiser, May 3, 1900. Hayden died in Winthrop on February 3, 1953.