Eleanor Raymond (1887–1989) was a Massachusetts architect specializing in residential projects. She produced a modern, multi-functional domestic architecture that remains relevant today. She is best known for designing one of the first solar-heated houses, the Dover Sun House, with Maria Telkes in 1948. In discussing her decision to pursue architecture, Raymond remembered herself as an independent young woman with a preference for individual creative work and a growing interest in gardens and buildings.

Eleanor Raymond at the Sun House in Dover, Mass., 1948. Harvard University Graduate School of Design, Frances Loeb Library, Special Collections

Birthplace

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Education

- Cambridge High and Latin School, 1905

- Wellesley College, A.B. 1909

- The Cambridge School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture for Women, Certificate, 1920

- The Cambridge School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (an affiliate graduate school of Smith College), M.Arch., 1936

Major Projects

- Cleaves house, Winchester, Mass., 1919

- TZE Society house, Wellesley College, Wellesley, Mass., 1922

- 112 Charles Street garden and house, Boston, 1923

- Raymond house, Belmont, Mass., 1931

- Peabody studio, Dover, Mass., 1933

- Peabody farm group, Dover, 1933

- Frost house, Cambridge, 1935

- Peabody plywood house, Dover, 1940

- Hammond compound, Gloucester, Mass., 1941

- Parker plywood house, Winchester, 1941

- Peabody masonite house, Dover, 1944

- Peabody Sun House, Dover, 1948

- Warner house, Ipswich, Mass., 1951

- Cove Chapel, Gloucester, 1955

- Nichols factory addition, Waltham, Mass., 1959

- Barr house, Haverhill, Mass., 1959

- Peabody Dave’s House, Dover, 1961

- Peabody Westville prebuilt house and garage, Dover, 1972

- Smith house, Biddeford Pool, 1973

Awards and Honors

- Trustee, Smith College, 1939

- Fellow, American Institute of Architects, 1961

- Special reception and conversation, An Evening With Eleanor Raymond, MIT, Cambridge, 1977

- Wellesley College Alumnae Achievement Award, 1982

Exhibitions of Work

- Architectural exhibition at Chicago’s World’s Fair, 1933

- Women in American Architecture, Brooklyn Museum, 1977

- Women in American Architecture, Hayden Gallery, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, 1977

- Eleanor Raymond: Architectural Projects, 1919–1973 (Doris Cole, Adjunct Curator), retrospective exhibition, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, 1981

- Ageless Perceptions IV: Senior Women in Architecture, SOHO20, New York, 1991

Firms

- Henry Atherton Frost and Eleanor Raymond, partnership, 1919–28

- Eleanor Raymond, Boston, 1928–

- Head of drafting room, Radar School, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, during World War II, 1940s

Professional Organizations

- Boston Society of Architects, member, 1924-89; secretary

- American Institute of Architects, member, 1924-89

Address of Last Firm

- 100 Memorial Drive, Cambridge, Mass.

Further Information

- The Eleanor Raymond Collection, Special Collections, Frances Loeb Library, Harvard University Graduate School of Design

- Eleanor Raymond Photographic Collection, Historic New England, 1919–1946 and 1981–1998

- The AIA Historical Directory of American Architects

- “The House of the Day After Tomorrow,” MIT Technology Review, MIT News Magazine

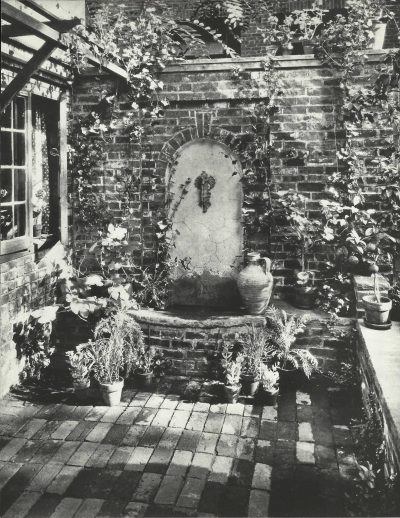

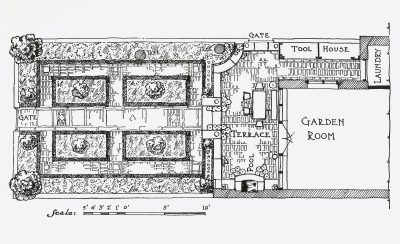

Eleanor Raymond, garden overview, 112 Charles Street Boston, Boston, 1923. Harvard University Graduate School of Design, Frances Loeb Library, Special Collections

Early Life and Education

Raymond was born and raised in Cambridge, Massachusetts, attended Cambridge Latin High School, and lived a comfortable life with her family. After graduating from Wellesley College in 1909, she traveled in Europe, visiting historic and contemporary sites in France, England, Germany, and Italy. Inspired by her travels and by her Wellesley landscape course, she wished to continue her studies of landscape architecture, and after some searching, she found the landscape architect Fletcher Steele, who was offering classes for Boston ladies. Raymond recalled that the instruction was primarily oriented toward young debutantes, but the information was there to be learned, and Steele was a well-qualified teacher and practitioner. Later, she wrote:

It wasn’t a very serious lecture series, but I liked him a lot and I liked his ideas. When that was over, I didn’t know what I could do, but I said to him, “Could I come down to your office and do just anything, scrub floors, just anything. I won’t ask for pay. I just want to be there to see what you do, drink it in.” He said, “Well, I don’t see how I can refuse to have you do that.” So that’s what I did. I went down to his office and worked there. The last thing I did was to make a drawing of stone paving for a terrace with different sizes of stones put together. Oh, I thought that was simply great.11The quotations of Eleanor Raymond included in this narrative are from an interview conducted by Doris Cole in the spring of 1981 in Cambridge, Mass. “An Interview with Eleanor Raymond” by Doris Cole appeared in Eleanor Raymond, Architectural Projects, 1919–1973 (Boston: Institute of Contemporary Art, 1981), which accompanied the Raymond exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, September 15 to November 1, 1981.

In 1917, at the age of 28 and eager to learn more about architecture, Raymond enrolled in the recently founded Cambridge School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. The training she received there was based upon the approach of the École des Beaux-Arts,with its concentration on the classic orders. Vignola’s handbook Regola delli cinque ordini d’architettura (1562) was the guide; capital and column, cornice and frieze were the order of the day. In 1920, after completing her studies, she received a certificate rather than an academic degree, since the school had no authority to grant one.

Eleanor Raymond, garden fountain, 112 Charles Street, Boston, 1923. House Beautiful Magazine/Hearst Communications, Inc.

Eleanor Raymond, garden plan, 112 Charles Street, Boston, 1923. House Beautiful Magazine/Hearst Communications, Inc.

Career

While still a student, Raymond opened an office with Henry Atherton Frost, her teacher and the co-founder of the Cambridge School. It is remarkable that Raymond, like many of her contemporaries, soon embraced modern architecture, developing her own style through the years. Her first commission, Cleaves House (1919), though it employed a classical order, had a straightforward simplicity. In 1928, she founded her own architectural firm in Boston. Although her design work soon transcended the rules of the schoolroom, she retained an appreciation for the basic principles of proportion and form throughout her career. As she explained in 1981:

I like the International Style of architecture which Gropius brought from Germany after World War II. I. M. Pei seems to follow this today. It is the simplicity that I like, not a lot of fussy detail. When I was starting out in architecture, fussy detail was rampant. The stripping away of unnecessary detail is what the International Style did and what I did in my own work. I like things simple.22Cole, “An Interview with Eleanor Raymond.”

Raymond’s attitude toward historical and contemporary architecture is best described in her book Early Domestic Architecture of Pennsylvania (first published in 1931 and reprinted in 1973). She was interested in the relationship between vernacular solutions and contemporary concerns, and sought timeless design principles that might be applied to future work. As she wrote in the book’s foreword, “I have not been actuated by history or archaeological interests.” It was with the active practitioner’s eye that she examined these anonymous structures in Pennsylvania, and historic architecture in general:

Anything I see that I like and I think is worth looking at hard influences my work. I think that the people who settled Pennsylvania had a better feel for design than the people who settled Massachusetts. When doing this book, I sent down a person from my office to work and live there for about six weeks. She was Miss Ruth Crook and I trusted her sense of design. She would find the buildings and I would go down and look at what she had found and decide what to have photographed . . . . Many of these buildings were done by the Amish . . . . They gave a lot of character to that part of Pennsylvania. I’m all for simplicity and was much impressed by their buildings.33Ibid.

Raymond chose to illustrate these design principles of simplicity and harmony of form in her book, and carefully studied and applied them to her own work. In projects as diverse as the renovation of the old Smith House and barn of 1926, the startlingly modern Raymond House of 1931, and the technically innovative Sun House of 1948, a consistency of design in Raymond’s relationship to early American architecture is evident.

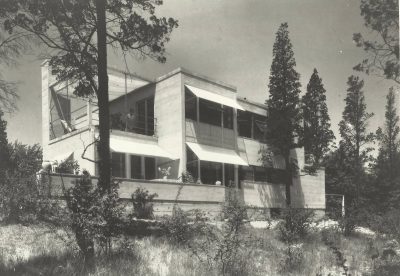

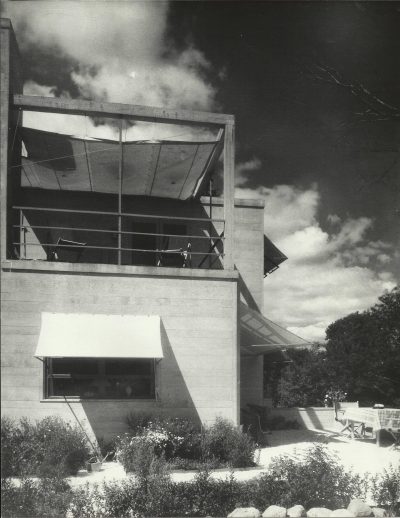

Eleanor Raymond, back elevation, Rachael Raymond House, Belmont, Mass., 1931. Harvard University Graduate School of Design, Frances Loeb Library, Special Collections

Eleanor Raymond, side elevation, Rachel Raymond House, Belmont, Mass., 1931. Harvard University Graduate School of Design, Frances Loeb Library, Special Collections

Raymond also had an ability to adapt and translate European architectural forms to a New England setting, understanding and assimilating their principles rather than simply copying their styles. Three examples, all in Massachusetts, are the Rachel Raymond House in Belmont (1931), the Peabody Sculptor’s Studio in Dover (1933), and the extensive remodeling of the Barnes House in Haverhill (1944). In an interview in 1981, she explained her approach:44Ibid.

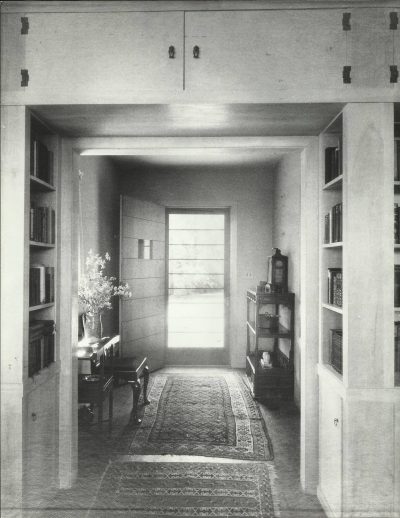

I did it [the Raymond House in Belmont] after Ethel Power and I had come back from Europe and visited the Bauhaus . . . . When Rachel wanted to build a house, we agreed upon the International Style. What we did was to keep the style, but to do it in local, New England, materials. Over there it was all concrete or stucco, never wood. Over here wood was what we used so much. I used rough-sawn matched wood boards for the outside finish of the walls . . . . I painted the doors the orangey-red of the Barberry fruit and stained the rough wood boards a soft gray-green . . . . I had been to California and had seen cloth used to shade open places so I did that on the open terrace. I used a new kind of window—they were factory windows actually . . . . It was easy to work with my sister, Rachel . . . . I feel as though that house is one of the best I ever did.55Ethel Power and Eleanor Raymond met at the Cambridge School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture and were lifelong friends. Power was an editor at House Beautiful magazine for several years in Boston and New York.

Eleanor Raymond, entry hall, Rachel Raymond House, Belmont, Mass., 1931. Harvard University Graduate School of Design, Frances Loeb Library, Special Collections

Raymond also explored the use of new materials and technology. With an architectural practice spanning from 1917 into the 1980s, she witnessed tremendous changes not only in American living patterns but also in construction materials and methods. Almost immediately, she embraced new technologies and began experimenting with new materials. One such project was the home for Mr. and Mrs. Gordon Parker in 1941, in which she used many of the plywoods, panels, and experimental products manufactured by their company.

Eleanor Raymond, rear elevation, Peabody Plywood House, Dover, Mass., 1940. Harvard University Graduate School of Design, Frances Loeb Library, Special Collections

Eleanor Raymond, side elevation, Peabody Plywood House, Dover, Mass., 1940. Harvard University Graduate School of Design, Frances Loeb Library, Special Collections

Three other technically innovative projects—Plywood House (1940), Masonite House (1944), and Sun House (1948)—were all done for the same client, the sculptor and art patron Amelia Peabody. In each house, Raymond incorporated technology into a broader continuum of concerns and values in American architecture. When asked how the project for the Sun House got started, she explained:

I had worked on other buildings for Amelia Peabody in Dover and for Godfrey Cabot’s granddaughter or daughter, now Mrs. Bradley. She told me about Maria Telkes, who was working at MIT under a Godfrey Cabot grant and trying to make sunlight turn into electricity or into sun heat, and introduced me to Maria Telkes. Of course, Maria was enthusiastic about trying out glauber salts, which she had discovered would store heat . . . . Well, Amy Peabody loved everything new. And she became interested. Finally, she said, “I’ll give you some land out in Dover and you can build a house and try this out.” That was pretty exciting for me. So from then on I would take Maria out in my car and she would look at the skylights on factory roofs . . . . In the winter she would see that some of them had angles which would hold snow . . . . But she wanted it vertical. So that’s what we did. We built the house and some of Maria’s relatives, who had escaped from Bucharest, when Hitler came along, lived in the Sun House . . . . So that was quite interesting, too.66Cole, “An Interview with Eleanor Raymond.”

Eleanor Raymond, south elevation, Peabody Sun House, Dover, Mass., 1948. Harvard University Graduate School of Design, Frances Loeb Library, Special Collections

Maria Telkes (left) and Eleanor Raymond in front of the Peabody Sun House, designed by Raymond, Dover, Mass., 1948. Harvard University Graduate School of Design, Frances Loeb Library, Special Collections.

As a woman of her time, Raymond was largely limited to commissions for personal homes, but it was nonetheless work she enjoyed. Speaking of “The Most Fascinating Job in the World—Building Houses,” she wrote:

Everybody is interested in houses because everybody has to live in one, and also because the house that children are brought up in means so much to them all their lives. If it has a good play area . . . if the outdoors offers space allocated to swing and sand box, the child will remember that house and that childhood with pleasure all his life. Furthermore, parents will do the same if frictions related to living together are removed as far as possible.77“Eleanor Raymond ’09 Builds Houses.” Wellesley Alumnae Magazine, March 1953, 164.

Raymond believed that domestic architecture was an important practice for young women architects. She noted that women’s traditions lie with the domestic in the broadest sense—including how people live and work, and the effect of the physical environment on everyday life. Her projects, whether houses, barns, piggeries, studios, factories, or gardens, encompassed the full range of concerns that she found essential to the built environment.88This profile is adapted from the essay “Eleanor Raymond” by Doris Cole that appeared in the book Women in American Architecture: A Historic and Contemporary Perspective, ed. Susana Torre (New York: Whitney Library of Design and Watson-Guptill, 1977), 103–7.

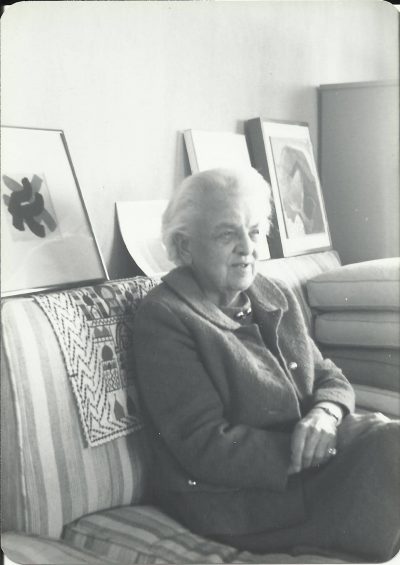

Eleanor Raymond in her apartment at 100 Memorial Drive, Cambridge, Mass., 1980 © Doris Cole