Alice Constance Austin (1862–1955) was a self-taught designer, feminist, and socialist. Her unrealized plans for the cooperative colony of Llano del Rio, California, included kitchenless houses with cooked food delivery and other innovative features intended to improve the lives of women. In 1935, she expanded upon these ideas in a pamphlet, The Next Step: How to Plan for Beauty, Comfort, and Peace with Great Savings Effected by the Reduction of Waste.11Subtitle as printed on cover of some editions; a different subtitle appears on the title page: Decentralization . . . How It Will Assure Comfort for the Family— Reduce Expense— and Provide for Future Development.

Alice Constance Austin showing model of house to Llano del Rio colonists, May 1, 1917. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Birthplace

Chicago, Illinois

Education

unknown

Major Projects

- House for herself and her parents, 2607 Puesta Del Sol Road, Santa Barbara, Calif., circa 1888

- Ideal city design for Llano del Rio Colony, near Palmdale, Calif., circa 1916

Further Information

- Walter Millsap papers, The Paul Kagan Utopian Communities Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

- Alice Constance Austin, Diary and Photographs, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Diary covers 1873–1882

- The Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif., holds records for the Llano del Rio Colony and the papers of its founder, Job Harriman

Sponsored by

Jill Lerner, FAIA

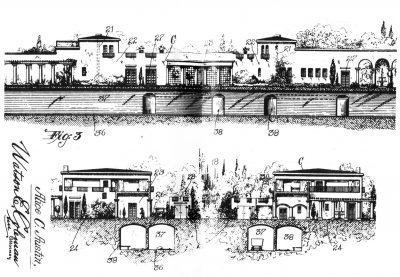

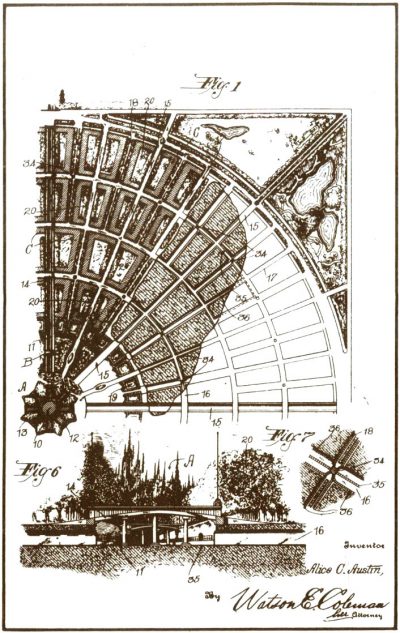

Sketches of an ideal city from a patent application, Alice Constance Austin, inventor. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Early Life and Education

Austin was born in 1862 in Chicago, Illinois, the only daughter of Joseph Burns Austin and Sarah Leavitt Austin. Her father was involved with railroads and mining. She had two older brothers, William Lawrence Austin and Cecil Kent Austin, and her first cousin on her mother’s side was Cecelia Beaux, the artist.22Birthdate and family information from “Joseph Burns Austin” family tree on Ancestry.com (accessed September 24, 2014). Alice Constance Austin’s date of birth is given there as March 24, 1862. No birth certificate was found for that date in Chicago. Her birth year was confirmed in U.S. Census of 1900 and 1910. The death certificate on file in Los Angeles County gives her birth date as March 24, 1862. Father listed occupation as mining in 1900 Census. The family traveled widely in the United States and Europe—England, Belgium, Germany, France, Italy. Little is known about her education, but she gave her occupation as “teacher” on some occasions, and friends suggested she had a gift for languages.33Her occupation is “schoolteacher” in the 1900 Census; “none” in 1910. In the 1908 city directory of Santa Barbara, she is secretary pro-tem of the Santa Barbara Society of Natural History. In a 1922 voter registration list, she is “dsgnr & bldr.” at 501 Buena Vista Street in Los Angeles. In the 1930 Census, at age 68, she is listed as “teacher, private school,” living in Los Angeles as a lodger with the family of Robert K. Williams, a former Llano colonist, next-door to Walter Millsap, also a former colonist. Millsap’s papers, part of the Kagan Collection at the Beinecke Library at Yale, include “Alice Constance Austin” and “Constance Austin’s Housing Concept” (WA-MSS S-1737) as well as photographs of plans and patent applications. Sharon Culver-Rease showed the author photographs of Austin’s travel journal headed “Alice Constance Austin. Lyons January 9th, 1873,” covering 1873 to 1882, now owned by the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. She was not trained as an architect, although a Llano colonist suggested she was inspired by Pullman, Illinois, and by workers’ housing she saw in Europe. Her interest in Ebenezer Howard suggests she may have lived for a time in England.

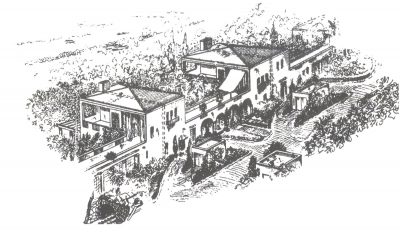

Axonometric drawing of two houses showing underground tunnels from Austin, The Next Step (1935)

Career

Austin designed a house for herself and her parents in Mission Canyon, Santa Barbara, in 1888. Her best-known project is an unbuilt design from 1915 to 1917 for an ideal socialist city. In her plans for the cooperative colony of Llano del Rio, located north of Los Angeles near Palmdale, California, and in The Next Step, Austin articulated an imaginative vision of life in a socialist, feminist society.44Alice Constance Austin, “The Socialist City,” series of articles, The Western Comrade, 4–5, 1916–17; Austin, The Next Step: How to Plan for Beauty, Comfort, and Peace with Great Savings Effected by the Reduction of Waste (Los Angeles: The Institute Press, 1935). Drawing on the communitarian socialist tradition in the United States, the Garden City movement in England, and the feminist consciousness of her time, she proposed a city of kitchenless houses. She believed that dwellings without kitchens would free women from the drudgery of unpaid domestic work and that the substantial economies achieved in residential construction of this kind would permit the development of extensive public facilities, including community kitchens and kindergartens.

Around 1915, Austin started to develop her plans for an ideal city. Job Harriman, a prominent Los Angeles lawyer and Socialist Party member who was the organizer of Llano del Rio, served as Eugene Debs’s running mate on the Socialist presidential ticket in 1900, and he waged a strong campaign for mayor of Los Angeles in 1911. After he lost that election, Harriman called upon his supporters, chiefly workers, farmers, and small businessmen, to build a cooperative colony in the Antelope Valley. Most of the community’s actual buildings were rough structures of wood or adobe, but Harriman invited Austin to visit the colony to present her ideas—in the form of drawings, models, and articles—to several hundred residents who wanted something better than the land speculator’s Los Angeles they had left behind. She told them: “The Socialist City should be beautiful, of course; it should be constructed on a definite plan . . . thus illustrating in a concrete way the solidarity of the community; it should emphasize the fundamental principle of equal opportunity for all; and it should be the last word in the application of scientific discovery to everyday life, putting every labor saving device at the service of every citizen.”55Alice Constance Austin, “Building a Socialist City,” The Western Comrade 4, no. 6 (October 1916): 17. The colony hired a draftsperson to draw up her plans for a circular city of ten thousand people inscribed within one square mile of land.

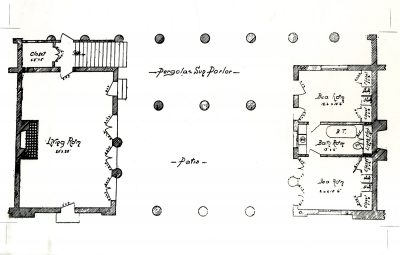

Plan of courtyard house from Austin, The Next Step (1935)

Criticizing the “suburban residence street where a Moorish palace elbows a pseudo-French castle, which frowns upon a Swiss chalet,” Austin proposed courtyard houses of concrete construction.66Ibid. Built in rows, these houses would express “the solidarity of the community” and emphasize the equal access to housing that a socialist town government could support. Austin allowed for personal preferences in the decoration of her houses, providing renderings of alternative schemes. She also set aside land for future architects’ experiments (how many utopians are this thoughtful?) as well as land for those colonists who wished to build conventional single-family dwellings.

Austin’s designs emphasized economy of labor, materials, and space. She criticized the waste of time, strength, and money, which traditional houses with kitchens required, and the “hatefully monotonous” drudgery of preparing 1,095 meals a year and cleaning up after each one.77Alice Constance Austin, “The Socialist City,” The Western Comrade 5, no. 2 (June 1917): 14. In her plans, hot meals in special containers would arrive from the central kitchens to be eaten on the dining patio; dirty dishes would then be returned to the central kitchens. In the other areas of the house, she provided built-in furniture and rollaway beds to eliminate dusting and sweeping in difficult spots, heated tile floors to replace dusty carpets, and windows with decorated frames to do away with what she called that “household scourge,” the curtain. Her affinity with the Arts and Crafts movement is apparent in her hope that producing these window frames, “delicately carved in low relief on wood or stone, or painted in subdued designs,” could become the basis of a craft industry at Llano, along with the construction of furniture in local workshops.88Ibid.

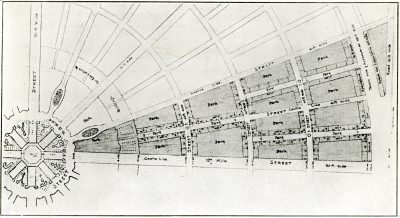

Plan of part of a proposed garden city, from Austin, The Next Step (1935)

Each kitchenless house would be connected to a central kitchen (serving one thousand people and staffed by paid workers, both women and men) through a complex underground network of tunnels. Railway cars from the center of the city would bring cooked food, laundry, and other deliveries to connection points, or “hubs,” from which small electric cars could be dispatched to the basement of each house. The centers would also include kindergartens. Although this elaborate physical and social infrastructure was obviously going to be very expensive, Austin argued for the economic and aesthetic advantages of placing all gas, water, electric, and telephone lines underground in the same tunnels as the residential delivery system. She also believed that eliminating all business traffic from the center would produce a more restful city. Residents could access the center on foot. Public delivery systems could handle all their needs, and goods coming to the city could arrive by air at a centrally located air-freight landing pad. Private automobiles—yes, every family was to have one—would be used chiefly for trips outside of this town of ten thousand souls, perhaps to neighboring towns built on the same plan.99For a full account of the Llano design, see Dolores Hayden, Seven American Utopias: The Architecture of Communitarian Socialism 1790–1975 (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1976), 288–317. She also suggested that the circular road around the town could be used for automobile races.

Sketches of an ideal city from a patent application, Alice Constance Austin, inventor. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Austin’s houses were never constructed by the Llano del Rio colony. Austin, Job Harriman, and the colonists encountered many disappointments at Llano: they were tricked by a land speculator; their proposed irrigation system failed; and some of the colonists finally relocated to Louisiana, where the colony survived until 1938. Austin stayed in southern California, refined her plans, tried to patent some of her ideas, and waited until 1935 to publish them as The Next Step. She was seventy-three. By then, planning for the Greenbelt Towns was part of the New Deal, and perhaps she thought cooperative communities were viable once again.

Austin was part of an American and British movement for material feminism, activist women who called for “a grand domestic revolution.” Melusina Fay Peirce of Cambridge, Massachusetts, first argued the need for community kitchens, laundries, and bakeries in 1868. She and Marie Stevens Howland of Hammonton, New Jersey, developed the complementary idea of kitchenless houses and child care centers.1010For Peirce, Howland, and their material feminist followers whose ideas were central to Austin’s designs, see Dolores Hayden, The Grand Domestic Revolution: A History of Feminist Designs for American Homes, Neighborhoods, and Cities (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1981). Beginning in the late 1880s, plans for cities of kitchenless houses abounded in futurist fiction such as Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward: 2000 to 1887, a book that Job Harriman admired and possibly the reason he invited Austin to Llano.1111Edward Bellamy, Looking Backward: 2000–1887 (1887; Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1967). In Chicago, Austin might have seen the model of kitchenless row houses designed by Mary Coleman Stuckert displayed in the Women’s Building at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. In 1898, Charlotte Perkins Gilman voiced her support in Women and Economics: “We are going to lose our kitchens!”1212Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Women and Economics (1898; New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1966), 245, 267, 269; also see Charlotte Perkins Gilman, “What Diantha Did,” fiction serialized in The Forerunner I, no. 1 (November 1909) to I, no. 14 (December 1910); Charlotte Perkins Gilman, “Professional Housekeeping,” California Outlook, June 21, 1913; Rob Wagner, “A Unique Mélange of Red and Black,” The Western Comrade I, no. 1 (October 1913): 235–36. Gilman had an impact on Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City movement in England, where several kitchenless projects were constructed at Letchworth, Welwyn, and Hampstead around 1910.1313Hayden, The Grand Domestic Revolution, 230–37. A comparison of Ebenezer Howard’s diagrammatic plan for a Garden City with Austin’s diagram for Llano shows Howard’s undeniable influence on her basic layout, but while his kitchenless dwellings were built as small enclaves within larger cities of conventional homes, she took this idea much further, creating an entire city of homes without kitchens and adding the necessary infrastructure.1414Edward Bellamy, Looking Backward: 2000–1887 (1887; Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1967).

This leap to urban scale was Austin’s major achievement. In her confident presentation, one sees the optimism of the suffragist era when feminists believed that far-reaching and drastic changes in women’s situation would result from winning the vote so long denied them. Because nurturing work—whether done by women or by men—still poses spatial and economic challenges for contemporary societies, Austin’s city can be read as a set of questions for the future, as well as a feminist socialist utopia from America’s past. Recently, young artists in California have celebrated the colony’s hundredth anniversary with a series of projects titled “Squaring the Circle: Llano del Rio Centennial,” including one called “The Next Step.”1515https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/squaring-the-circle-llano-del-rio-centennial

The author would like to acknowledge Sharon Culver-Reese, Diane Favro, and Geneva Morris for their help with sources for this essay.