During her brief, sixteen-year career as an architect, Lilian Jeannette Rice (1889–1938), a native of Southern California, was acclaimed for her attention to site and local context. She is best known for the Spanish Colonial-style buildings she designed in the 1920s and ’30s for Rancho Santa Fe, an upper-class community in the San Diego metropolitan area.

Lilian J. Rice as lead truck driver, thwarting a strike by hauling crews that threatened the beginnings of the Rancho Santa Fe project, 1923. Courtesy of Diane Welch

Birthplace

National City, San Diego County, California

Education

- School of Social Sciences, University of California, Berkeley, Bachelor of Letters, 1910

- University of California, Berkeley, Postgraduate teaching certificate, 1911

- Coursework in marine engineering and naval architecture, Mare Island, Calif., 1918

Major Projects

- Civic Center (architectural designer for Santa Fe Land Improvement Company through Requa and Jackson), Rancho Santa Fe, Calif., 1923–28

- Juan María Osuna Adobe (restoration and remodeling for new owners, Alfred and Blanche Barlow), Rancho Santa Fe, 1925

- Christine Arnberg Residence, La Jolla, Calif., 1928

- Rancho Santa Fe (residential and commercial projects, master-planned community), Rancho Santa Fe, 1928–38

- San Dieguito Union High School, Encinitas, Calif., 1935

- Juan María Osuna hacienda and grounds (remodeling of second Osuna adobe for new owner, Bing Crosby), Rancho Santa Fe, 1934, 1937

- Ecke Ranch House, Encinitas, 1935

- Ruben H. and Elizabeth Fleet Residence, La Jolla, 1935

Awards and Honors

- AIA Honor Award, for Christine Arnberg Residence, La Jolla, Calif., 1928

- House Beautiful Award, for the Wohlford Residence, Escondido, Calif. (demolished), 1932

- AIA Honor Award, for ZLAC Rowing Club, San Diego, Calif., 1933

- AIA Honor Award, for mixed-use office and apartment building, La Valenciana Apartments, Rancho Santa Fe, Calif., 1933

- National Register of Historic Places (ten buildings in Rancho Santa Fe; one home in La Jolla)

Firms

- Hazel Wood Waterman, San Diego, as draftsman, circa 1910–15

- Requa and Jackson, San Diego, as draftsman and designer for Rancho Santa Fe project, 1921–23

- Santa Fe Land Improvement Company, as resident supervisory architect for Rancho Santa Fe project, 1923–28

- Lilian Rice, Architect, 1929–38

Professional Organizations

- Secretary College Women’s Club, San Diego, 1912

- Rancho Santa Fe Association, Art Jury Member, 1928

- San Diego Chapter of the American Institute of Architecture, 1931

Location of Last Office

La Valenciana Apartments, Paseo Delicias, Rancho Santa Fe, Calif.

Further Information

- Architectural Drawings Collection, San Diego History Center

- Diane Y. Welch private collection of Lilian Rice photographs, Krisel project business papers, oral histories, and Rice’s college scrapbook, 1909–10, San Diego

- Harriet Rochlin Collection of Material about Women Architects in the United States

- “Historic American Buildings Survey, Rancho Santa Fe,” National Park Service

- Kile Morgan Local History Room, National City Library, National City

- Offices of the Rancho Santa Fe Association, Rancho Santa Fe

- Olive Chadeayne Architectural Papers, 1925–56, MS1990-057: Special Collections, University Libraries, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

- Rancho Santa Fe Historical Society, Rancho Santa Fe

- San Diego Historical Center, Research Library & Archives, Curatorial Collection Division

Lilian J. Rice, high school class portrait, circa 1905. Courtesy of Diane Welch

Early Life and Education

Rice was born on June 12, 1889, in National City, California, just south of San Diego and ten miles north of the Mexican border.11Lilian Rice’s date of birth is confirmed by her birth certificate. Unfortunately, the official document at the County Recorder’s Office in San Diego has been misplaced. However, there is a copy of it in the Harriet Rochlin Collection of Material about Women Architects in the United States, 1887–1979, at the University of California, Los Angeles, Department of Special Collections (coll. no. 1591). I am indebted to librarian Jeffrey Rankin for providing a digital copy of it for my use. Her parents, Julius Augustus Rice (1854–1933) and Laura Steele Rice (1854–1939), natives of Vermont, had moved there in 1879. Her father encouraged Rice to pursue her education, and her mother fostered her artistic sensibilities; in school, she excelled in both math and the arts. Julius, an educator who served as a teacher, principal, district superintendent, and member of the State Board of Education, received a “life diploma” (the most permanent and desirable form of teacher certification) from the California State Board of Education for his contributions to local schools;22Theo F. Johnson, “The Evolution of Our Schools,” National City News, June 26, 1915. Julius A. Rice was granted a life diploma by the State Board of Education, Sacramento, on July 3, 1888; San Diego Union, August 6, 1888. he also worked in real estate and insurance during the boom periods of the early twentieth century. Laura was an amateur artist who painted oil miniatures and remodeled the Rice family home designed by Elizur Steele, her uncle. Growing up in National City, Rice was exposed to the region’s rich Spanish colonial heritage on land dotted with long-abandoned, crumbling adobe dwellings, and she saw the Hispanic influence on architecture eclipse the Victorian style, for which her uncle was noted.

Rice began college at the University of California, Berkeley in 1906,33Transcripts of Lilian J. Rice’s University of California, Berkeley records (1906–18). the same year as the San Francisco earthquake.44The Daily News, San Francisco, April 18, 1906. Along with her fellow students, she brought aid to those displaced and housed in tents in the foothills of Berkeley; this willingness to help others continued into her adulthood, despite her busy practice. Rice excelled in her studies and enjoyed a rich social life.55According to Rice’s U.C. Berkeley college transcripts, she passed all her courses, including descriptive geometry, which several students found too difficult. In early 1909, she joined the school’s Architectural Association and, after being appointed to one of its leadership positions, took on the responsibilities of organizing exhibitions, recording the accounts, and attending to the tea service.66University of California Architectural Association Minutes, the College of Environmental Design Collection, Environmental Design Archives, University of California, Berkeley, April 23, 1909: 65.

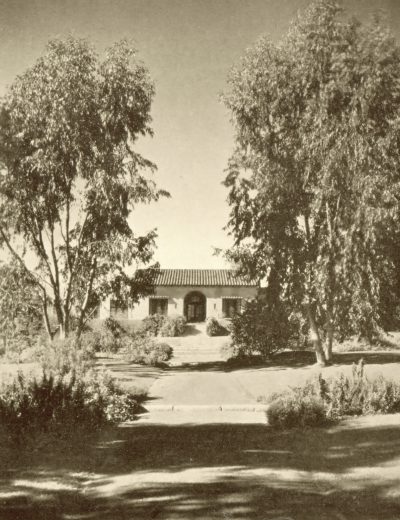

Lilian J. Rice, La Morada (the guest house) Civic Center, Rancho Santa Fe, 1922–23. Courtesy of Diane Welch

Lilian J. Rice, circa 1910. Courtesy of ZLAC Rowing Club

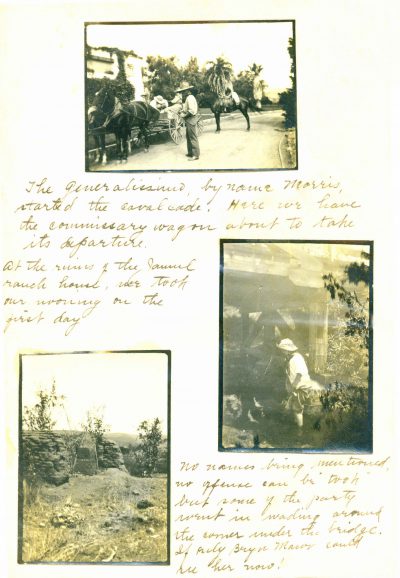

One page of Lilian J. Rice’s private journal depicting a back country trip to Rancho Jamul, San Diego County, Calif. The image to the right shows Rice with her skirt hitched up, wading in a stream, circa 1910. Courtesy of Diane Welch

After graduating in May 1910, Rice went back to National City to care for her ailing mother but returned to U.C. Berkeley that autumn to take a one-year postgraduate course in teaching. Two of her friends and fellow students, Grace E. Morin and Walter E. Steilburg, were hired to work in the office of Julia Morgan in San Francisco after they graduated, an opportunity that might have perhaps been Rice’s as well, had her mother’s illness not required her presence at home.

Career

There are very few records documenting the years of Rice’s life between 1910 and 1922. Rice’s sorority publication in 1910 included a brief notice about her work: “Lilian Rice ’10 teaches mathematics in National City. She continues her work along artistic lines for her own enjoyment and has sent the girls of the chapter name cards and similar favors.”77“Miss Lilian [sic] Rice has finished the necessary practice teaching and received her high school teaching diploma Thursday evening”; National City News, June 17, 1911. The publication also mentioned that Rice had designed an English-style residence for a lady, giving no details about the project.88To Dragma of Alpha Omicron Pi Fraternity (of which Rice was a member). Of note is that Rice was affectionately nicknamed Pinky (also Pink or Pinkie) by those close to her. To Dragma of Alpha Omicron Pi Fraternity, page 94 (1910): “We have contributed more than our share of artists, for there was Lilian Rice, ’10, and Grace Morin, ’10, who always comprised the art staff in years gone by. We miss ‘Pink’ or Lilian more than we can express.”

Rice received her teaching diploma in 1911.99To Dragma of Alpha Omicron Pi Fraternity. She taught geometric drawing in her home town and was then hired to teach at San Diego High School.1010School Annuals held in San Diego High School Archives, San Diego, Calif. At the same time, Rice worked part-time as a draftsman for Hazel Wood Waterman.1111Mary F. Ward, “An interview with Waldo D. Waterman,” San Diego Historical Society Oral History Program, January 1971, 5. A protégé of Irving Gill—now lauded as the father of the modernist style of architecture in Southern California—Waterman made her own mark in San Diego as the city’s first female architect, although she was never licensed. In her capacity as a teacher, Rice influenced several up-and-coming architects, including Sam Hamill, FAIA, who later designed the Del Mar Fairgrounds and the San Diego County Administration Building.1212Harriet Rochlin, interview of Sam H[am]ill (talking about Rice), in Harriet Rochlin Collection of Material about Women Architects in the United States, 1887–1979, coll. no. 1591, box 6, folder 40, UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections, University of California, Los Angeles. See also Sam Hamill on Lilian J. Rice, box 6, folder 57.

In 1921, Rice was hired as an associate in the office of Richard Requa and Herbert Jackson, resulting in a significant advance in her professional life.1313In her letter of application to join the AIA, Rice wrote on June 8, 1931, “I was a draftsman for the firm of Requa and Jackson, Architects, of San Diego for about two and a half years; for five years I had charge of the architectural department for the Santa Fe Improvement Company at Rancho Santa Fe; and since February of 1929 have been practising [sic] as a licensed architect.” Also of note is that the roster of the California State Board of Architectural Examiners indicates that Rice was only the tenth woman in the state to receive her license at a time when there were 1,650 men licensed as architects. Requa and Jackson had recently been commissioned to design a Civic Center on the former Spanish landgrant of Rancho San Dieguito in San Diego County (a property of nearly 9,000 acres), a project that they passed on to Rice, their most capable associate. When the designs for the Civic Center site plan and buildings were completed, she turned to the residential aspects of the highly restricted, upscale subdivision, which was renamed Rancho Santa Fe in mid-1922. With other more lucrative projects to work on in San Diego, Requa gave her full creative and supervisory control over the entire project in 1923, and she was soon directing a large team of workers.1414Ruth R. Nelson, “Rancho Woman Architect Only One in County: Miss Lilian [sic] Rice Patronized by Many for Spanish and California Home Designs,” San Diego Union, January 28, 1930, 4, col. 1. In 1925, Rice was also hired by Alfred and Blanche Barlow to restore and expand an 1831 adobe in Rancho Santa Fe that they had bought; it had been owned by the first mayor of the Pueblo of San Diego, Juan María Osuna, after he secured control of the Rancho San Dieguito land grant in 1836.

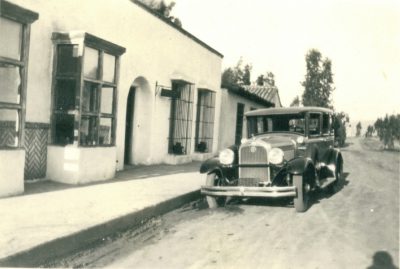

Lilian J. Rice, the house of Louise Spurr-Badger (manager of the service station), Paseo Delicias, Civic Center, Rancho Santa Fe, 1922–23. Courtesy of the Spurr Family

Lilian J. Rice (highlighted) with her team of workers in front of her office in the Santa Fe Land Improvement Co. Administration Block, Paseo Delicias, Civic Center, Rancho Santa Fe, Calif. Designed by Rice, 1922–23. Courtesy of Phoebe Marrall

Lilian J. Rice, entrance to the service station in the Garage Block, Paseo Delicias, Civic Center, Rancho Santa Fe, 1922–23. Courtesy of the Spurr Family

Lilian J. Rice, Garage Block, Paseo Delicias, Civic Center, Rancho Santa Fe, 1922–23. Hand-colored photograph. Courtesy of the Spurr Family

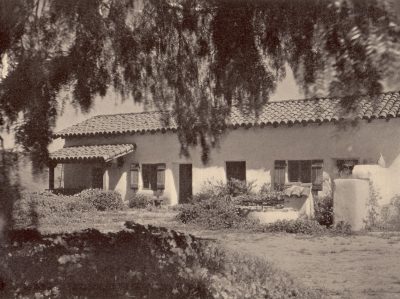

The derelict Silvas/Osuna adobe in 1925 before Lilian J. Rice’s restoration for Alfred and Blanche Barlow, Rancho Santa Fe. Courtesy of the Barlow Family

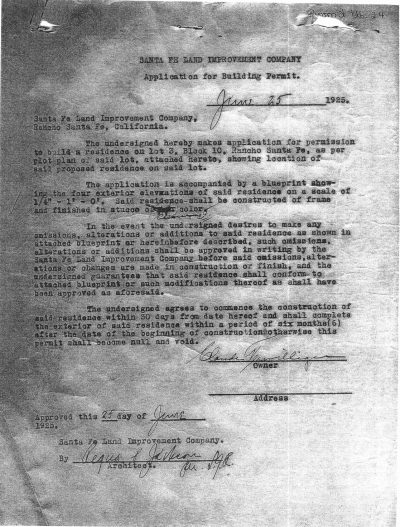

Building permit for the Claude and Florence Terwilliger residence, June 25, 1925, and signed by Lilian Rice per Requa and Jackson Architects. Requa and Jackson Architects received the commission to develop Rancho Santa Fe, Calif. Rice, an associate of the firm but not then licensed, designed the buildings and took over the entire project by 1923.

Lilian J. Rice, the Claude and Florence Terwilliger residence. San Elijo, Rancho Santa Fe, 1925. Courtesy of Don Terwilliger

Lilian J. Rice, view looking north east of Rice’s rowhouses, 1926. Courtesy of the Spurr Family

Lilian J. Rice, the restored Silvas/Osuna adobe for the Barlow family, circa 1927. Courtesy of the Barlow Family

Rice’s architectural design work was strongly influenced by the philosophy of the Hillside Club, a Berkeley-based organization of architects and women homeowners who joined forces in 1902 in this scenic Northern California city. Together, they strove to protect the natural environment and held a steadfast belief that buildings should be subservient to the land. The Hillside Club’s most noteworthy maxim was that a home was “landscape gardening around a few rooms for use in case of rain.” Many of Rice’s buildings demonstrate this simple aesthetic principle: rather than dominate the Southern California landscape, they enhance it in a quiet way. Even her fine estate homes, designed for some of the nation’s wealthiest elite, show a marked restraint in their decorative treatment.

Lilian J. Rice, the estate home of the Millard family during framing, Rancho Santa Fe, 1927. Courtesy of the Ragan Family.

Lilian J. Rice, the Millard home, with daughter Natalie and pet dog, Rancho Santa Fe, circa 1927. Courtesy of the Ragan Family

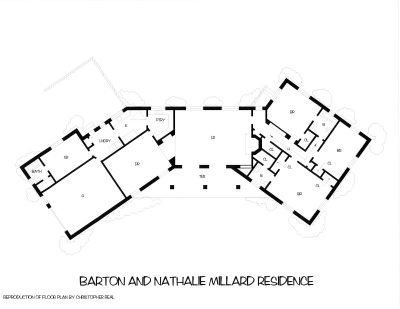

Plan of the Millard home, recreated by Christopher Real. Courtesy of Diane Welch

From 1923 until her death in 1938, Rice remained in Rancho Santa Fe, but she traveled often. Trips to Spain were especially influential, and after a trip to southern Spain in 1925, she wrote:

Beginning always with a provision for practicality and achieving a true artistry, the charm of Spanish architecture has endured and will endure. Its underlying motive is honesty—honesty in plan, honesty in materials, and a sincere attempt to meet the requirements imposed by environment. A winding street in Spain is picturesque—but the winding street was developed from the necessity for protection from invading armies and not to produce an effect.1515Lilian Rice, article in Rancho Santa Fe Progress 2, no. 4 (October 1928): 8. Photographs from Rice’s trip are contained in the archived papers of a local historian, Ruth R. Nelson, a close friend of Rice’s and an early resident of Rancho Santa Fe. She was the wife of Sydney Nelson—Sinnard’s assistant, who later took over Sinnard’s role as manager of Rancho Santa Fe—and wrote newspaper columns for the Rancho Santa Fe Progress, and for the San Diego Union Tribune. Nelson’s archive is held at the Rancho Santa Fe Historical Society. Some scholars have said that Rice never went to Spain and that her inspiration for her Spanish designs came from Requa’s visits there in 1926 and 1928. However, the historical record counters this claim. Ship manifestos recorded on the website ancestry.com show that Rice traveled to Europe in 1925. Her return trip was on the S.S. Aquatania, which sailed from Cherbourg, France, to New York on November 21, 1925.

Lilian J. Rice, La Valenciana Apartments, mixed-use complex, Paseo Delicias, Civic Center, Rancho Santa Fe, 1928. Rice had her office here and used upper-story apartments for her male draftsmen. Courtesy of the Ragan Family

Lilian J. Rice, exterior of Hamilton Carpenter estate home, El Mirador, Rancho Santa Fe, 1928. Photograph by Darren Edwards

Lilian J. Rice, interior of Hamilton Carpenter estate home, El Mirador, Rancho Santa Fe, 1928. Note the workmanship in the ceiling treatment, a signature Rice architectural detail. Photograph by Darren Edwards

In 1928, coinciding with yet another trip to Spain by Requa, Rice opened her own office in Rancho Santa Fe. She designed most of the community’s new architecture, both residential and commercial, but also began to design homes outside Rancho Santa Fe.1616Some architecture historians regard Rice as having been unethical in her business practices—that she deliberately deceived her clients into believing that she was the architect of record for the master-planned community of Rancho Santa Fe before she received her license in 1929. However, this charge was mistaken, since no license was needed in the 1920s for the work that she did for the Santa Fe Land Improvement Company as resident supervisory architect from 1923 to 1928. See Diane Y. Welch, The Life and Times of Lilian J. Rice, Master Architect (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 2015). In those independent projects, she was free to depart from the restrictions set down by the Ranch Association’s covenant mandates and to move away from the Spanish Colonial style and closer to the organic approach popularized by Frank Lloyd Wright. For example, the Marguerite Robinson House in La Jolla, which she designed in 1929, is integrated into the site, utilizing rock as an integral design feature.1717Judith Paine, “Lilian Rice,” in Women in American Architecture: A Historic and Contemporary Perspective, ed. Susana Torre (New York: Whitney Library of Design, Watson-Guptill, 1977), 110; and author’s visit to the Marguerite Robinson House in 2005. Other houses in San Diego County and in Riverside County are more eclectic in style. It is clear that Rice placed her clients’ wishes first, while attempting to respond to the setting and locale. In 1937, she wrote an article titled “What Our Homes Should Mean to Us,” explaining her objectives:

The first requirement is to make the home livable even before the general appearance is considered. . . . In general, a home does represent a species of language. It reflects the story of the life and the habits of the people who live within its walls, the material that was available at the time of the building, the tools that were used and the taste of the builder. . . . Always will it be one of the human desires to live in surroundings which the individual chooses and likes—a place which combines conveniences with a pleasing appearance—and, if he is in a measure satisfied with the results, he proudly calls it HOME.1818Lilian Rice, “What Our Homes Should Mean to Us,” Rancho Santa Fe News 2 no. 1 (April 1937).

Lilian J. Rice, Marguerite Robinson home as it looks today, Ludington Place, La Jolla, Calif., 1929. Photograph by Paul Body

Lilian J. Rice, interior of Marguerite Robinson home, Ludington Place, La Jolla, 1929. Photograph by Paul Body

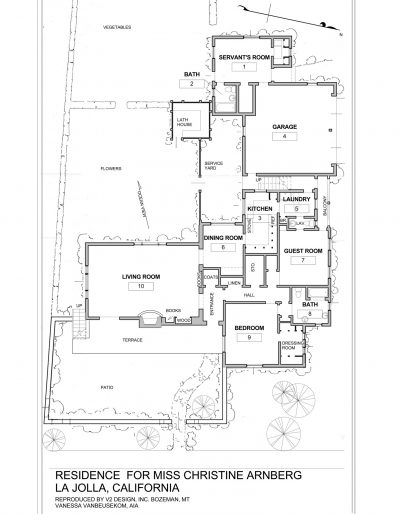

Lilian J. Rice, plan of the Christine Arnberg home, recreated by Vanessa Vanbeusekom, Folsom Drive, La Jolla, 1928. Courtesy of Diane Welch

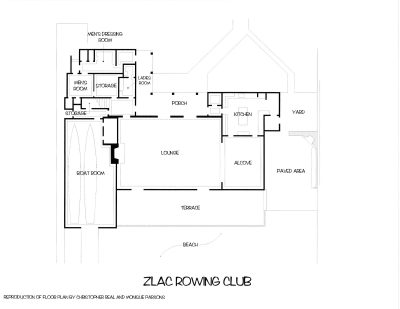

Lilian J. Rice, plan of ZLAC Rowing Clubhouse, recreated by Monique Parsons and Christopher Real. Courtesy of Diane Welch

Lilian J. Rice, ZLAC Rowing Clubhouse as it looks today, San Diego, Calif., 1932. Photograph by Diane Y. Welch

The 1930s proved to be Rice’s most industrious years despite the economic hardships of the Great Depression. In 1932, she designed a boathouse and clubhouse for the ZLAC Rowing Club, an all-female organization founded in 1892, of which she was a member and past president.1919ZLAC Rowing Club archives, at 1111 Pacific Beach Drive, San Diego, Calif., 92109. It won her an award from the San Diego chapter of the American Institute of Architects. In 1935, she began work on the Paul Ecke Ranch home in Encinitas, on the Pacific coast a few miles west of Rancho Santa Fe.2020Ecke Ranch Archives, California State University, San Marcos, at 333 S Twin Oaks Valley Road, San Marcos, Calif., 92078. That same year, Rice also designed the local high school, a WPA project, for the newly-formed San Dieguito Union High School District in Encinitas.2121Information about the San Dieguito Union High School (now named San Dieguito Academy) is held in the archives of the San Dieguito Heritage Museum, Encinitas, California, 92024. Three years later, she designed an elementary school for what is now known as the Chula Vista Elementary School District just south of National City; after she died, it was renamed the Lilian J. Rice Elementary School in her honor.

Lilian J. Rice, former Ecke Ranch House, Saxony Drive, Encinitas, Calif., 1935. The ranch house is now part of Leichtag Commons, Encinitas, Calif. Courtesy of the Ecke Family

Many of Rice’s clients were successful and wealthy; they included industrialists, financiers, movie producers, and Hollywood stars. One of the most famous was Bing Crosby. In 1934, he purchased the former Juan María Juan Osuna hacienda in Rancho Santa Fe and its surrounding acreage, where he could have a state-of-the-art ranch for his race horse business, Binglin Stables.2222Bing Crosby, “Our Little Ranch in the West,” California Arts and Architecture 48 (October 1935): 24–25. He commissioned Rice to do an extensive remodeling of the existing stables and the second Osuna adobe on the property and to design a new race track and paddock.2323Martha B. Darbyshire, “Rancho Santa Fe Ranch House; the Bing Crosbys at Home in Their California Hacienda,” Arts & Decoration (December 1935).

Lilian J. Rice, presentation drawing for the proposed, un-built Krisel estate home, Via de Fortuna, Rancho Santa Fe, circa 1935. Photograph by Ron Krisel. Courtesy of William Krisel

That same year, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford’s attorney, Alexander Krisel, hired Rice to design an estate complex in Rancho Santa Fe, which included a hacienda and extensive horse trails.2424During the 1920s and ’30s, Krisel and his family lived in Shanghai, China, where he was the exclusive distributor in the Far East for United Artists films (co-founded in 1919 by Fairbanks, Pickford, Chaplin, and D. W. Griffith) and the commissioner of the U.S. Court for China, 1928–34, and then practiced law there until 1937, when the Krisels moved to Beverly Hills, California. Sources: the paragraph “At the Krisels” in The Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury, online at <https://archive.org/stream/ldpd_11033152_002/ldpd_11033152_002_djvu.txt>; and “William Krisel and George Alexander in Hollywood, 1937–1956,” online at <https://socalarchhistory.blogspot.com/2011/01/william-krisel-and-george-alexanders.html>. Previously, in 1926, Fairbanks and Pickford had commisioned Rice to design several utility buildings to service their orange groves, planted on Block K of Rancho Santa Fe, along with several hundred acres of the former Lusardi property. Although the home was never completed, Rice’s influence was significant: William (b. 1924), the youngest of the Krisels’ three sons, became an architect and had a successful career in Southern California.2525Bill Krisel, conversation with the author, Rancho Santa Fe, California, March 24, 2009. Over the course of his career, Krisel designed approximately 30,000 buildings there and as many as 10,000 elsewhere; see Miyoko Ohtake, “Q&A with Illustrious California Architect William Krisel,” online at <https://www.dwell.com/collection/qanda-with-illustrious-california-architect-william-krisel-8a279842>.

Despite the Depression, Rice’s career flourished. However, in July of 1938, Rice was diagnosed with ovarian cancer and died six months later, on December 22.2626Certificate of Death from the County of San Diego Recorders Office; San Diego Union, December 24, 1938: 9, col. 2; and San Diego Union, December 25, 1938: 4, col. 3. “Services for Lilian [sic] Rice, 52 [sic], for 15 years a resident of Rancho Santa Fe, who died in a local hospital Thursday, will be conducted Tuesday, 2 p.m. in Bradley-Woolman chapel. Cremation will follow. Miss Rice was born in National City. She is survived by her mother, Mrs. Laura S. Rice, and a brother, J. A. [sic] Rice, National City.” Olive Chadeayne, who worked in Rice’s office at that time, took over the practice after Rice’s death, but was unable to sustain the business. Unfortunately, most of her personal archives and professional records were discarded.

In January 1939, Rice’s fellow members in the San Diego AIA honored her memory by establishing a fund to provide scholarships for architecture students, starting with an initial donation of five hundred dollars in seed money. According to an article in 1940 in the Oakland Tribune, other generous donations soon followed.2727The article reported that “friends of the late Lilian J. Rice, class of 1910, $1382.89 contributed under sponsorship of the San Diego Chapter of the American Institute of Architects for establishment of the Lilian J. Rice Memorial Fund, to be used for loans to junior, senior and graduate students in the School of Architecture.” Oakland Tribune, February 9, 1940: 18, col. 3. The fund was not maintained, however, most likely owing to the onset of World War II and subsequent difficulties in continuing its management.

Though now largely forgotten, Rice created much significant work in her brief career and always remained true to her philosophy that a building should harmonize with the land. In a 1928 article, “Architecture, a Community Asset,” Rice explained her approach to designing Rancho Santa Fe:

With the thought early implanted in my mind that true beauty lies in simplicity rather than ornateness, I found real joy at Rancho Santa Fe. Every environment there calls for simplicity and beauty—the gorgeous natural landscapes, the gently broken topography, the nearby mountain. No one with a sense of fitness, it seems to me, could violate these natural factors by creating anything that lacked simplicity in line, in form, and color.2828Lilian Rice, “Architecture: A Community Asset,” Architect and Engineer 94, no. 1 (July 1928): 43.