In 1937, the Pittsburgh Courier recognized Ethel Bailey Furman (1893–1976) as the first female African American architect to practice in the state of Virginia.11“Architect,” Pittsburgh Courier, January 23, 1937. During the course of her career, which spanned over four decades, Furman designed more than two hundred buildings, including single-family residences, church projects in Central Virginia, and two chapels in Liberia.

Ethel Madison Bailey Furman

Birthplace

Richmond, Virginia

Education

- Private tutoring, 1910s–20s

- Chicago Technical Institute, 1944–46

Major Projects

- Wilder House, Richmond, Va., 1923

- Fourth Baptist Church addition, Richmond, 1961

- Edward and Barbara Snead Residence, Goochland County, Va., 1968

- Springfield Baptist Church, Hanover County, Va., 1976

- E.B. Clark House, Richmond, n.d.

- Dolores Snead Residence, Goochland County, n.d.

- St. James Baptist Church, Goochland County, n.d.

- Union Baptist Church, New Kent County, Va., n.d.

- Union Hope Baptist Church, King William County, Va., n.d.

Awards and Honors

- East End Civic League Walter Manning Citizenship Award, 1954

- Afro-American Honor Roll, Richmond, 1959

- Ethel Bailey Furman Memorial Park, Richmond, 1985

- Library of Virginia’s Virginia Women in History Honoree, 2010

Firms

- Michael J. Bailey, Contractor & Builder, Architect, E. B. Furman, Richmond

- Mrs. Ethel B. Furman, Architect–Notary Public, Richmond

Ethel Furman’s childhood home, 3025 Q Street, Richmond, Va., designed and built by her father Madison J. Bailey. Photograph by Phil Riggan. Richmond Times Dispatch, December 25, 2015

Early Life and Education

Ethel Madison Bailey Furman was born on July 6, 1893, in Richmond, Virginia, to Madison Jefferson and Margaret Mary Jones Bailey. Her career path began when she was still a child, as she accompanied her father, one of the first licensed African American contractors in Richmond, to various job sites from Virginia to New York. Even before her formal architectural education in the 1920s, Furman’s father had enlisted her as a draftsperson in his firm. Despite her practical skills and experience, as an African American woman Furman was subject to the inequitable policies of early-twentieth-century universities and was unable to attend an established architecture school. However, Madison Jefferson recognized his daughter’s interest and evident talent in the field and arranged for a private tutor in New York to train her in architecture.

Furman married her first husband, William H. Carter, in Philadelphia, in 1912, and had two children, Madison and Thelma.22Jessica Breeden, “Ethel Bailey Furman,” Manuscript of AIA Lecture, 4th Baptist Church, Church Hill, Virginia, April 16, [1997?], 6. Their brief marriage ended in divorce, and by the mid-1910s Furman had returned to Richmond with the children and rejoined her father’s practice. She married Joseph Furman in 1918 and had a third child, J. Livingston, soon after. In 1920, Furman, together with her husband and children, and her father and his wife, moved to New York City, setting up a household on Seventh Avenue. According to an article in the Black weekly New Journal and Guide, Furman began to receive private tutoring from Edward R. Williams, a well-regarded Black architect who had studied at the Hampton and Tuskegee Institutes. After completing her studies with Williams, she received a diploma stating that she was a certified architect. In 1923, she returned to Richmond.33Bill Jordan, “Richmond Merry-Go-Round,” New Journal and Guide, September 11, 1937, A12. The author is indebted for this source to Kate Reggev, “Hanging Her Shingle: Early Female Architects On Starting Their Own Firms,” Madame Architect, March 29, 2021.

Negro Contractors’ Conference, Hampton Institute, Hampton, Va., February 14, 1928. Ethel Furman is sitting in the center of the front row. Ethel Bailey Furman Papers, Library of Virginia

Throughout her life, Furman remained a devoted wife, loving mother, and cherished member of the Church Hill community, where friends and neighbors nicknamed her “Peachy.”44Breeden, “Ethel Bailey Furman,” 7. She was, as reporter Bill Jordan noted, especially known for “encouragement of women in all fields of work.”55Jordan, “Richmond Merry-Go-Round,” A12. Still, she valued her architectural career as much as her other roles, and continued to work in partnership with her father, developing a thriving design-build practice that she would maintain well after his retirement in the mid-1940s.

Career

Although her private training in New York and early partnership in her father’s firm had proved more than sufficient to secure Furman’s professional success within the local community, in 1944, at the age of 51, she sought to supplement her education with a degree in drafting from the Chicago Technical Institute, perhaps through a correspondence course. Her architectural training there probably introduced her to a more modern aesthetic than her previous private lessons had in the 1920s. Modernist principles, as well as an understanding of popular domestic building types, would figure significantly in her future practice.

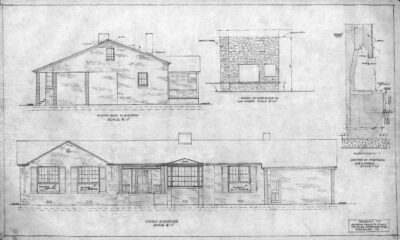

Ethel Furman, architectural drawing of the Mr. and Mrs. Junium A. Snead residence, Glen Allen, Virginia, n.d. Ethel Bailey Furman Papers, Library of Virginia

Furman received her degree in 1946, reentering the field just as the postwar American building boom had begun. In this newly prosperous market, her previous relationships with area contractors proved instrumental for advancing her career. In fact, those ties and the bonds she had forged in Richmond’s African American community through civic work, political action, and religious commitments made publicity of her services unnecessary. Furman would go on to design numerous private suburban homes and churches in the Richmond area as well as large steel and concrete structures including hotels and department stores.66“Virginia’s Only Woman Architect,” Baltimore Times-Dispatch, July 6, 1946.

She also designed two projects for small churches in Liberia—international commissions she obtained through her involvement in the Lott Carey Missionary Circle Community Improvement League.77Breeden, “Ethel Bailey Furman,” 7.

Ethel Furman, Fourth Baptist Church Educational Building, Richmond, 1961. Photograph by Christopher Carroll

Ethel Furman, entrance to the Fourth Baptist Church Educational Building, Richmond, 1961

The homes and churches Furman undertook varied in aesthetic, as the commissions dictated. Some projects, such as a colonial-style house for E. B. Clark of Richmond, in which Furman was charged with mimicking a colonial Williamsburg home that Clark considered his “dream house,”88Breeden, “Ethel Bailey Furman,” 7. demonstrated her attentiveness to her clients’ visions. Others, such as the Wilder House—the childhood home of Virginia’s first African American governor, L. Douglas Wilder—reflected her sensitivity to the architectural fabric of Church Hill. Still others, such as her design for the educational wing of the Fourth Baptist Church in Richmond (1961), represented her knowledge of (and perhaps, propensity for) mid-century modernism.

The churches she designed for clients on the rural outskirts of Richmond, such as Union Hope Baptist in King William County, Springfield Baptist in Hanover County (1976), and Union Baptist and Mount Nebo Baptist in New Kent County, are remarkable for their refined simplicity and efficiency of means. Although those churches share a basic massing and interior layout—a long, rectangular meeting space organized around a single processional aisle, with pews on either side—and a tripartite exterior articulation, their choice of materials and details lend each project an individual identity.

Ethel Furman, Mount Nebo Baptist Church, Barnhamsville, New Kent County, Va., n.d. Photograph by Sandra Tibbs Blake

Ethel Furman, St. James Baptist Church, Goochland County, n.d. Photograph by Christopher Carroll

Furman’s designs for suburban single-family home reflect popular housing trends of the era. Residences for both Dolores Snead and Edward and Barbara Snead (1968) of Goochland County, Virginia, used similar materials (brick veneer, aluminum siding) and exterior details (sash windows flanked by decorative shutters, low gable roofs, bay windows), although their size, interior layout, and program varied according to the individual families’ needs. In all of her projects, Furman provided practical, efficient, and well-designed spaces, regardless of her clients’ budget or stylistic preferences; for this reason, she not only was renowned within the building community, but also acquired many loyal clients—including seven members of the large Snead family, all of whom commissioned homes from her.

Ethel Furman, Dolores Snead residence, Goochland County, Va., n.d. Photograph by Christopher Carroll

In spite of Furman’s professional success, however, she was forced to confront the sexism and racism that permeated postwar America. Building officials regularly contested her construction documents or designs when she submitted them under her name, while they easily accepted her work when presented by a male colleague. Nevertheless, Furman refused to accept this as a solution and persisted in presenting her drawings on her own terms.99Breeden, “Ethel Bailey Furman,” 10.

Outside of the architectural realm, Furman addressed other issues facing the African American community: she helped register Black voters in the 1960s, participated in a seminar held by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) on discriminatory housing policies in Virginia, co-founded the East End Civic League, and committed herself to the overall health of the Church Hill neighborhood.1010Breeden, “Ethel Bailey Furman,” 8. Such community service, in addition to her successful practice, is a testament to her tenacity in overcoming the discriminatory practices of the early- to mid-twentieth-century United States.

That Ethel Bailey Furman was purportedly the first architect of both “her sex and race”1111“Architect.” in Virginia is, of course, a laudable accomplishment during a period characterized by rampant inequality, yet it threatens to lessen her legacy as both an architect and civic leader. Regardless of race or gender, Furman’s prolific design practice and active community service affirm her significance to the architectural profession.

Portrait of Ethel Madison Bailey Furman, n.d. Ethel Bailey Furman Papers, Library of Virginia

The author would like to thank Jacqueline Taylor for her helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article.