Sibyl Moholy-Nagy (1903–1971) was an architectural historian, critic, and teacher, who played an important role in the reassessment of modern architecture after World War II. Besides writing an important book about her husband Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s work, she wrote numerous articles and books, bringing an increased attention to vernacular architecture and urban issues.

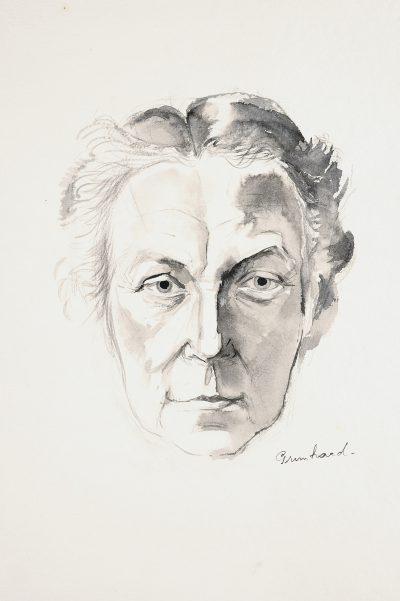

Portrait of Sibyl Moholy-Nagy by Simon Grunhard, 1967. Belgian Royal Library

Birthplace

Dresden, Germany

Education

Miscellaneous courses at various German universities

Awards and Honors

- Arnold W. Brunner Grant, The Architectural League, New York City, 1953

- John Guggenheim Fellowship, Guggenheim Foundation, 1967

Academic Positions

- Librarian, later head of the Humanities and Lectures Division, Institute of Design, Chicago

- Lecturer, Rudolf Schaeffer School of Design, San Francisco

- Professor of Architectural History, Pratt Institute, New York, 1951–69

- Visiting Professor, Columbia University, New York, 1970

Further Information

- Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (Sibyl and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy papers, 1918–1971; holdings on microfilm)

- Museum of Modern Art, New York City (correspondence with Philip Johnson)

Sponsored by

Architecture Research Office

Early Life and Education

Originally named Sibylle Pietzsch, Sibyl Moholy-Nagy was the youngest daughter of the Dresden architect Martin Pietzsch. She grew up in a well-to-do bourgeois family with one brother and two sisters. Her education was not very extensive; she finished school at age seventeen. After unsuccessful stints as an apprentice in the book business and as an actress, she married, in 1929, the Frankfurt intellectual and industrialist Carl Dreyfuss, a close friend of Theodor Adorno. In 1931, she left Frankfurt for Berlin, where she attempted a career as a script writer, which seems to have worked out better than her previous choices. In Berlin, she met Bauhaus photographer and sculptor László Moholy-Nagy, with whom she started an affair. In 1933, their first daughter, Hattula, was born; in 1935 (after both their divorces had come through), they married in London, where their second daughter, Claudia, was born in 1936. They left London for Chicago in 1937. László Moholy-Nagy directed the Institute of Design in Chicago, one of the first schools in the United States where the design principles of the Bauhaus were the basis for an innovative curriculum for artists and industrial designers. As his assistant, Sibyl was responsible not only for their home and the education of their children, but also for driving him around, editing his manuscripts (e.g., the influential Vision in Motion), and running the Institute’s summer school. During the same period, her efforts to embark upon a literary career of her own led to the publication of a novel, Children’s Children, published in 1945 under the pen name S. D. Peech. When László died in 1946, she came to terms with her grief by writing his biography, Experiment in Totality, published in 1950, with a foreword by Walter Gropius.

S.D. Peech (Sibyl Moholy-Nagy’s pseudonym), Children’s Children, 1945. Book cover designed by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. Courtesy of Hilde Heynen

Career

Near the end of Moholy’s life, Sibyl had been nominated head of the Humanities and Lectures Division in the Institute of Design. She capitalized on this experience by starting a teaching career as an architectural historian. After a short interlude at Bradley University in Peoria, Illinois, she moved with her children to the West Coast, where she taught at the Rudolf Schaeffer School of Design in San Francisco and at the University of California, Berkeley. In 1951, she received a half-time appointment at Pratt Institute in New York, where she climbed the ranks to become, in 1960, the first woman to be a full professor there. She managed to pass as a highly educated intellectual, as if she had credentials from famous German universities. In 1969, she resigned from Pratt after a conflict with the other faculty about the future direction of the school. She spent her last year of teaching, 1970, as a visiting professor at Columbia University.

Through her numerous writings and lectures, Sibyl Moholy-Nagy became an outspoken presence on the postwar architectural scene in the United States. She played a pivotal role in the growing criticism of modernist architecture, and she was one of the driving forces behind the increasing interest for the urban and historical dimensions of architecture. Moreover, she was remarkably open toward other cultures, especially those in Latin America, writing about architecture in Mexico, Peru, Venezuela, and Brazil.

Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, Experiement in Totality, 1950. Courtesy of Hilde Heynen

Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture, 1958. Courtesy of Hilde Heynen

After her biography of Moholy-Nagy, which is still valuable today as a firsthand account and vibrant interpretation of his life and work, she embarked on a study of American vernacular architecture; this research led to her book, Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture, published in 1957. She turned to vernacular architecture in order to offer an alternative for contemporary architects, showing them that the anonymous architecture of the past could offer sources of inspiration for designing better contemporary homes; this architecture, she believed, displayed the exact qualities that were lacking in the mass-produced houses of the 1950s. Imitation, however, was not the point she was advocating. In comparing a spec house in Levittown with the seventeenth-century Abraham Hasbrook House in New Paltz, New York, of which it was a pasteboard replica, she ridiculed the intentions of the developer. Whereas the original example was a marvel of functionality and good design for its location and its times (which implied poor heating provisions and vulnerability to Indian attack), the replica was a cheap reproduction of forms that lacked any climatic or functional justification. What she advocated, therefore, was that architects should commit themselves once again to the design of homes, not leaving this critical task to the care of building promoters and real estate developers, and that they should seek inspiration in the intrinsic qualities (not the external forms) of the vernacular houses of the past. She wrote, “To provide the home as an ideal standard is still the architect’s first cause, no matter how great and rewarding are his other contributions to monumental and technological building. . . . As those builders of old, the architect of today has to create an anonymous architecture for the anonymous men of the Industrial Age.”11Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture (New York: Horizon Press, 1957), 23.

Abraham Hasbrouck House, New Paltz, N.Y., published in Sibyl Moholy-Nagy’s Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture, 1957, 39. Photograph by Sibyl Moholy-Nagy. Special Collections and Archives, UCSC

© Hattula Moholy-Nagy

Typical street in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, published in Sibyl Moholy-Nagy’s Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture, 1957, 123. Photograph by Sibyl Moholy-Nagy. Special Collections and Archives, UCSC

© Hattula Moholy-Nagy

Gradually, she became more and more critical of modern architecture, turning against those who believed in technology as the ultimate savior of architecture and stressing that learning from the past remained paramount for making good buildings and good cities. In a 1961 article in Perspecta (the Yale architectural journal), she discussed the works of four architects in America—Philip Johnson, Paul Rudolph, Louis Kahn, and Eero Saarinen—in terms of their engagement with the past. It was clear for her that by this point the modernist prescription of ignoring history and always starting from scratch was taking its toll. Although each of the four architects she discussed dealt with history in his own way, she recognized a clear danger in their historicist gestures, believing that they risked making architecture into a superficial display of ornaments and motives of the past (a prefiguration of what would later be called postmodern architecture):

Architecture today has a high potential which will be wasted if it is not combined with the stubborn fight of the mature years to keep a principled integrity inviolate. The reevaluation of the past might indicate a genuine revolution—it might also indicate no more than a fad for want of a better copy.22Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, “The Future of the Past,” Perspecta 7, no. 1 (1961): 65–76.

After this, her commentary became increasingly critical—and more sarcastic. She clearly lost the belief that modern architecture could live up to its high potential, and that American culture would be able to absorb the European influence without betraying its own qualities. This critical attitude culminated in her 1968 article, “Hitler’s Revenge.” It opened:

In 1933 Hitler shook the tree and America picked up the fruit of German genius. In the best of Satanic tradition some of this fruit was poisoned, although it looked at first sight as pure and wholesome as a newborn concept. The lethal harvest was functionalism, and the Johnnies who spread the appleseed were the Bauhaus masters Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe and Marcel Breuer.33Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, “Hitler’s Revenge,” Art in America (September 1968), 42–43.

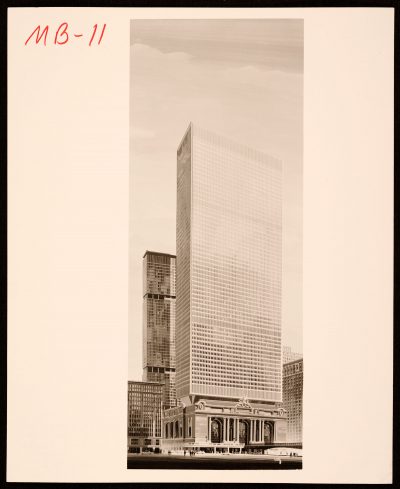

Marcel Breuer, proposal for a Grand Central Air Rights Building, New York, 1969. Archives of American Arts

She claimed that the import of German functionalism had destroyed the vitality of indigenous American architecture, and that functional architecture was no longer providing the urban and architectural qualities that it once had in such abundance.

Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, Matrix of Man: An Illustrated History of Urban Environment, 1968. Courtesy of Hilde Heynen

Her 1968 volume, Matrix of Man: An Illustrated History of Urban Environment, was a major contribution to contemporary debate on the city. In giving her book the title Matrix of Man, Moholy-Nagy conveyed her conception of the city as the source and origin of civilization. For her, the city contained everything that was worthwhile in human culture; it nurtured and gave form to the intellectual and emotional lives of the individuals who live in it. This humanist approach targeted all those who looked to science and technology to solve the city’s problems. In the introduction, she wrote: “The technocratic illusion that man-made environment can ever be the image of a permanent scientific order is blind to the historical evidence that cities are governed by tacit agreement on multiplicity, contradiction, tenacious tradition, reckless progress, and a limitless tolerance for individual values.”44Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, Matrix of Man: An Illustrated History of Urban Environment (New York: Praeger, 1968), 12. Throughout the book, Moholy-Nagy stressed the importance of landscape, regional climate, tradition, culture, and form. She repeatedly referred to the city as a symbol of power, but also as a symbol of human aspiration and participation. The city for her was a generative force, capable of molding people and civilizations, bringing forth creative energies and interconnectedness. One of the most interesting concepts that she introduced was what she called “architectural urbanity.” The term referred to the idea that urbanity was not a matter of a two-dimensional layout of streets and axes, but rather resulted from the interplay of three dimensions—the buildings along the streets and squares being a decisive element.

Sibyl Moholy-Nagy was also an acclaimed teacher. As a former actress, she knew how to captivate the attention of her students, and she left an indelible mark on many of them. The obituaries written by her friends and colleagues unanimously praised her for her intense devotion to teaching. Paul Rudolph, for example, recalled how “her students loved her, partially because she demanded their best, but also because they sensed that all her life, Sibyl Moholy-Nagy grew, becoming ever more aware, ever more committed and passionate in her prejudices, giving of herself to students, friends, and, above all, architecture.”55Paul Rudolph, “Sibyl Moholy-Nagy,” Architectural Forum 134, no. 5 (June 1971): 29.

Portrait of Sibyl Moholy-Nagy by Simon Grunhard, 1967. Belgian Royal Library